Park History

Jefferson Square Park

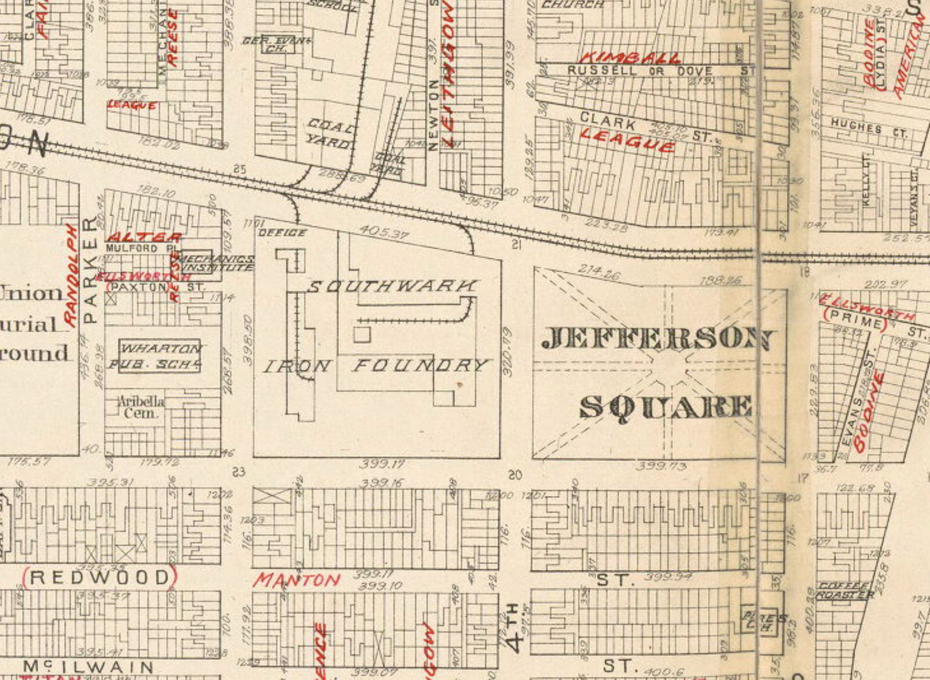

Named after U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, Jefferson Square is a Classic 19th Century American Strolling Park. It was originally constructed in the early 19th century when the area was part of the Village of Southwark. The village and the park became part of the City of Philadelphia during the Great Consolidation Act of 1854, when all counties, boroughs and towns within Philadelphia County merged to become the City as we know it today.

During the Civil War the park was used by the Union Army as an encampment site. Afterwards the park was reconstructed using the Rittenhouse Square Park plans. The park’s granite retaining walls and pillars are identical to those installed at the same time in Rittenhouse Square.

The Park as Part of Southwark

To best understand the history of the park, it is helpful to see how it fit into the community over many years. In the early 18th century, the area near the park was settled by a mix of Swedish, Dutch and English settlers. It became known as the Village of Southwark, named after a section of London known for its shipbuilding activity. Though not yet part of the City of Philadelphia, Southwark incorporated as a Borough of the County of Philadelphia on March 26, 1762. Southwark became part of the City of Philadelphia under the Consolidation Act of 1854 when all townships, villages and boroughs within the County of Philadelphia were simultaneously merged into the City of Philadelphia. Philadelphia’s neighborhood names, such as Southwark, often came from the former names of these townships and boroughs.

When Philadelphia served as the capital of the U.S. (1790-1800), some streets in Southwark were named or renamed to identify with the capital city it now neighbored. Prime Street was renamed to Washington Avenue. Federal Street was created and named. Jefferson Avenue (now Passyunk Avenue) was created. The park was named after President Thomas Jefferson. Southwark was growing both in population and as an economic force. Installing a public park was an ideal way for a growing borough to welcome more prominence and prosperity.

The Civil War Era

Like its namesake in London, Southwark primarily consisted of businesses and residents dedicated to the shipbuilding trades. The Wharton & Humphries Shipbuilders, located at the “foot of Federal Street” (now Front & Federal Streets), built the frigate “Philadelphia” and other ships for the US Navy for use in the American Revolution. This same shipyard became the US Naval Shipyard in the early 19th century. Parts of the piers also served as immigration ports. Local legend has it that these immigration ports welcomed more immigrants to the U.S. than Ellis Island in New York, but that statement would have to be confirmed with the passenger records at the Philadelphia Port of History Museum for veracity. Because of its ports, Southwark played a prominent role during the Civil War. Southwark became the easiest port in Philadelphia to receive and disembark troops and supplies. Another advantage of the Southwark ports over those slightly north in Philadelphia was the amount of open land available to establish encampments for troops, prisons for prisoners of war, and army hospitals, etc. Thousands of troops, horses and supplies were moved through Southwark’s ports daily during the Civil War.

Because of the volume of troops being moved in and out of the area, the need to feed this huge volume of men was fulfilled through the construction of “Refreshment Saloons”. These saloons were not bars or taverns like the current meaning that the term suggests, but instead were instead large buildings and tents which served food “cafeteria style” to hundreds of troops at a time. Like the army hospitals, they were largely staffed by local volunteer housewives who would cook, clean, nurse and feed troops for long hours each day. Refreshment saloons and volunteer hospitals lined Washington Avenue, Front Street and Water Street. Southwark residents became known as Civil War models of patriotism and volunteerism, and many soldiers wrote home about the great care and good food they received in Southwark. One diary contained a note taken from a soldier off a basket of cookies he was given, “Dear General, these cookies are for the sick soldiers. Should you or your officers take even one I should hope you choke of it.”

After the Civil War and Into the 20th Century

Following the Civil War, the Southwark section of Philadelphia grew as a thriving industrial corridor. Commercial train tracks were laid on Washington Avenue, allowing large manufacturers and merchants to move goods easily to and from the ports and by other rail lines. These large businesses encouraged both long-time and new immigrant residents to remain in the area to live and work, and the area population ballooned to large numbers.

By the mid-20th century, manufacturing in the U.S. began rapidly declining. More goods were now being moved by truck instead of trains, and the ports of Southwark and the many warehouses and factories in the area begun disappearing. These trends made a significant impact on the Washington Avenue corridor. The construction of the highway I-95 in the 1950’s also had an enormous impact on the residential sections of the area. The highway construction razed thousands of original Southwark homes that had fallen into decline. Southwark lost many original homes and buildings, was losing thousands of residents, and the commercial corridor fell into decline. Urban decay was becoming more noticeable and Jefferson Square Park was also reflecting these changes. Despite these elements of decline, enough businesses and families ultimately came to or remained in the area to enable it to survive.

By the 1970’s, the once northern section of Southwark became known as Queen Village and was transitioning into a trendy and desirable place to live. There was also an increasing awareness of the area’s history, and the Southwark National Historic District was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places on May 19, 1972. Though the original southern border of Southwark was Wharton Street, the Southwark U.S. Historic District’s southern border was declared to be Washington Avenue. The area south of Washington Avenue shortly thereafter became known as Pennsport.

The gentrification that began in Queen Village continues today to push south into Pennsport, with a new housing boom and the restoration of homes dating to the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Washington Avenue’s once commercial corridor has transformed into a variety of successful multicultural retail businesses and restaurants, largely Vietnamese and Mexican.

The Park Itself

The current park is what remains of its post-Civil War reconstruction. The park was originally constructed in early 19th century had star-like patterned walkways. During the Civil War, like other squares in Philadelphia, Jefferson Square Park was renamed Camp Jefferson and was deeded to the Union Army for use as an encampment site and parade grounds. The Square’s close location to the ports, the “refreshment saloons” and military hospitals made it an ideal location for military use. Advertisements in the Philadelphia Inquirer during the Civil War welcomed area residents to Camp Jefferson, particularly young men inclined to enlist, to see the daily displays of military weaponry and watch the performances of marching soldiers and bands.

Following the Civil War the park was re-deeded back to the City of Philadelphia. The City adopted a restoration plan for many of its parks previously used by the military. This plan called for a new classic style of park, known as strolling parks, which were designed solely for passive use activities like strolling, reading, etc. This design was especially desirable for squares and parks in urban areas were surrounded by homes with little or no yards or gardens. It enabled area residents to simply walk from their homes to a park for an enjoyable, relaxing time outdoors. This was believed to promote good mental and physical health. These classic park designs called for inviting entrances, walkways that were wide enough for two passing couples, a center “destination point” that was a circle or square with a statue or fountain, and ample benches and lighting. Jefferson Square Park, like other parks in Philadelphia such as Rittenhouse Square and Washington Square, were all reconstructed in the 1870’s using this design. Jefferson Square Park’s current walkway pattern, granite retaining walls and entrance pillars date to this 1870’s restoration. Early photographs of the park show that cast iron urns once decorated the top of all 16 entrance pillars at the park’s eight entrances. An 18th century Inquirer article, describing an explosion across the street from the park at the Merck & Company iron foundry (now Sacks Playground), notes that Jefferson Square Park’s decorative iron fencing was partially destroyed by the blast, evidencing that the park once had cast iron perimeter fencing. Cast iron urns and iron fencing were removed by the City from many parks for scrap iron drives in World War I and II. Photographs of Jefferson Square Park before World War II show the pillars with their urns. Photos after that war show the pillars with the urns gone. It is not certain when the fencing was removed.

The Rebirth of Jefferson Square Park

The park suffered hard times and was nearly demolished. When the community around the park and the Washington Avenue commercial corridor began to decline, the park was used less by area residents and correspondingly received less maintenance from the city. The decaying homes on the northern side of the park were removed by the 1970’s in favor of The Southwark Towers, which were three hi-rise towers for public housing. Unfortunately, the crime rate in and immediately surrounding the towers rose substantially and the condition of both the park and the surrounding community sank further downward. Illegal dumping in the park was common. Drug dealers and drunken gangs became the park’s primary users. The park was in such decline and disuse that by the 1980’s the city proposed removing the park in favor of an indoor recreation facility and basketball court. In opposition, a group of area residents formed the Friends of Jefferson Square Park and successfully saved the park from demolition.

Several driving forces then began to quickly reverse the area’s decline and revitalized the park. In response to increasing crime and problems in and near the three public housing towers, the city housing authority removed two of the three towers and replaced them in the 1990’s with attractive, well-run subsidized housing, and converted the remaining tower into a senior retirement residence. This immediately reduced many problems and further encouraged the gentrification of Queen Village to quickly and safely advance southward below Washington Avenue. To further encourage the advancing gentrification and eliminate urban blight south of the park, a middle-income housing development called the Jefferson Square CDC (taking its name from the park) formed around 2002 to replace hundreds of decaying homes with new homes. Adding to the southward gentrification was a growing trend among suburban resident to move to city neighborhoods that were adjacent to center city, making the area near the park a desirable urban place to live. Further, the city encouraged new home construction with a 10-year real estate tax abatement on all new city homes. All of these changes brought many new residents to the area and a new mix of users to Jefferson Square Park. Finding the park in need of maintenance and repairs, a group of new residents revitalized the dormant Friends of Jefferson Square Park, bringing many improvements to the park.

This renewed effort to restore and improve the park has led to a substantial renovation of Jefferson Square Park which began in 2007.

By Michael J. Toklish, Friends of Jefferson Square Park

April, 2007

Image at top of page: Bachmann, J., Weik, J. & P.S. Duval & Son. (1857) Bird’s eye view of Philadelphia. [Philadelphia John Weik] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress